|

“Once men turned their thinking over to machines in the hope that this would set them free. But that only permitted other men with machines to enslave them.” “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a man’s mind,” Paul quoted. … “But what the O.C. Bible should’ve said is: ‘Thou shalt not make a machine to counterfeit a human mind.’ … The Great Revolt took away a crutch,” she said. “It forced human minds to develop. Schools were started to train human talents.” Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam and Paul Atreides in Dune[1] [1] Frank Herbert, Dune, Chilton Company: Boston, Massachusetts, 1965, 12, 11-12. I have worked in the world of professional military education (PME) for about fifteen years and I have taught cadets as part of a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program at a university and I have taught brand new lieutenants and new captains at the U.S. Army Armor School (then at Fort Knox, Kentucky) and I have helped to shape the training and education of officers in several Middle Eastern countries and I currently teach new majors at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The standard use of the acronym PME is for professional military education. In this post I advocate for professional mentat education. Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune introduces the reader to a universe where human beings had ten thousand or so years earlier fought a war to defeat thinking machines – computers or robots with artificial intelligence. Humans developed three human replacements for the loss of thinking machines. One of those groups included people called mentats. These people were taught to understand probabilities and possibilities to include concepts of politics and strategy. I am not trying to make anyone a Dune nerd with this explanation. My point is that Western (and particularly American) professional military education (PME) needs to develop the equivalent of mentats today. I have intended to write this article for a very long time as I was frustrated by the failure of the U.S. officer corps to conduct wars more effectively during the Global War on Terrorism and I have regularly hoped to connect posting this with an anniversary of the withdrawal from Afghanistan and to explain how American PME had failed the nation in the past and what its responsibility is to the nation in the present. That is still one of the objectives of this piece. I have also listened to numerous discussions on how to bring artificial intelligence into the classroom of civilian schools and within PME. One morning, about a year ago I listened to a piece from NPR that was an interview with an associate professor from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania who requires students to use ChatGPT to write papers for his class.[1] I have noted in my current eleven year stretch of graduate level education that students arrive at my institution less and less prepared to have discussions of importance that require an understanding of history and less capable of refining and articulating their thinking in a written form. I have blamed this on the broader failures of the undergraduate education system. This NPR interview expressed just how degraded education has become. In short, it seems as if the body has forgotten the meaning and purpose of education. The purpose is not about product. The purpose is teaching process. We should be teaching people how to research, how to think, and how to articulate that thought in speech and writing. Too many people seem to think that colleges are involved in producing products and the argument in favor of artificial intelligence (AI) is that it helps average people produce better products. That is probably true, but in the process of placing emphasis on product, we are failing to teach the processes – the hows of learning – that truly matter down the road. The point at which I realized the interviewee was wrong was when he said that calculators didn’t make us worse at mathematics. Yes, they did. People are demonstrably worse at calculator-less computation today than humans were one hundred years ago because they don’t practice the skills and they quickly turn to a device to offer the easy solution. This makes people worse at a skill. For those who haven’t heard of ChatGPT, it is a chat bot that can write for a person. A person feeds in questions and the bot produces a paper of a specified length based off the parameters provided by the person. It has recently produced graduate school passing work. This isn’t wonderful. This is horrible. I am not a Luddite, by the way. I like and value technology. I use calculators. I also understand that using aids, of any sort, makes me weaker in that way. Crutches and wheelchairs facilitate and promote muscle and bone density atrophy. Crutches and wheelchairs are useful and even essential for some, but they should never be used by all, or we risk societal harm. My biggest concern regarding the involvement of AI in education is that it will cause thinking, like any other muscle using a crutch, to atrophy. What does this have to do with PME? We are not teaching people who manage societally sanctioned violence on behalf of the nation to do so properly. I question if the responsible institutions and organizations understand what such an education should include. I acknowledge that these are strong statements. I will give some examples to illuminate my assertions. I contend that the U.S. government, including the U.S. military, suffers from three sins of ignorance: ignorance of underlying logic, ignorance of narrative space, and ignorance of strategy. I will briefly explain each of the problems in turn. Underlying logic. I often ask students to explain the underlying logic for how to win a war. That request regularly gets blank looks and silence in response. I don’t blame the officers. No one has taught them to think about the logic which undergirds their doctrine or their approach to war, in general, or a war, in specific. I sometimes continue the discussion by asking students to explain the logic behind why defense is considered the stronger form of war or the logic behind a turning movement. Both of these lines of questioning often lead to informative discussions about why a force should or might conduct a specific type of operation. To explain what I mean by underlying logic, I will use the surge in Afghanistan that was initiated in 2009. What was the underlying logic for that effort? It goes something as follows in the forms of necessary steps and assumptions:

With each step of this logic trail there are problems, but this is a simplistically stated logic trail for why people believed the surge could work. Now, what are the problems with the logic trail? Most of this comes in the form of simple questions. First, did the Afghan people and the U.S. leadership either in the U.S. or in Afghanistan agree on the definition of good? Second, what was the distinction for the average Afghan villager between good and evil? Was that easily and obviously discernable in terms of the differences in behavior of the Taliban, the Afghan National Security Forces, or U.S. military personnel? Third, there was no good governance available to replace the evil governance even when the first three steps were achieved. That meant that the people never had the opportunity to be good such that they would reject future Taliban advances or assertions of authority. I hope that this little exercise causes some internal debate and argument. I expect that some readers will poke holes in it. That is what I want. I want readers and students to think through the underlying logic of a given philosophy or doctrine. We do not teach this, and we do not regularly discuss this and we definitely do not do this when planning operations, campaigns, or writing strategies. [1] Mary Louise Kelly, “'Everybody is cheating': Why this teacher has adopted an open ChatGPT policy,” National Public Radio [26 January 2023]. https://www.npr.org/2023/01/26/1151499213/chatgpt-ai-education-cheating-classroom-wharton-school [accessed 19 February 2024].

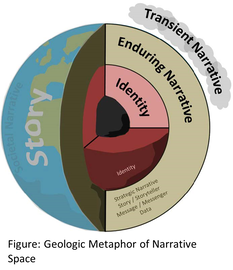

Narrative space has terrain, just as does physical space. Narrative space terrain is made up of ideas, concepts, humiliations, grievances, history, culture, language, religion, etc. that have different values in terms of shaping the thoughts, perceptions, and associated actions of people who reside in that narrative space. Narrative, for the purposes of this philosophical approach, includes social identity, enduring narrative and transient narrative. Figure [to right] captures the imagery of this concept in the form of a geologic metaphor in that social identity forms the core of how the society or culture sees itself and the most deeply rooted narrative structures. It is the bedrock of the later described narrative space. … Continuing with the geologic metaphor, narrative space terrain is constructed in much the same way as is physical terrain through basic processes of deposition, erosion and tectonic forces, which creates a narrative landscape or narrative shape/structure. Understanding narrative shape and structure is narrative morphology. These processes, as with their physical counterparts, happen over long periods of time or can happen in violent episodic events. The primary shapers of this space are events, ideas (people-thinkers) and actions (people-doers).[1] [1] Brian L. Steed, “Narrative Leads Kinetic Warfare,” Dangerous Narratives: Warfare, Strategy, Statecraft, Washington, DC: Narrative Strategies Ink, 2021, 23, 25. Understanding narrative space means understanding self, opponent, terrain, etc. It includes understanding the operational environment, but as expressed above it is more than the physical composition, disposition, and strength of the enemy and more than the intelligence preparation of the battlefield. For those who think this doesn’t matter, I include a quote from then LTG Douglas Lute who had been the person on the National Security Council responsible for coordinating the Global War on Terrorism through part of two different presidential administrations. He was quoted in a SIGAR (Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction) interview in 2015 saying the following: “I bumped into an even more fundamental lack of knowledge; we were devoid of a fundamental understanding of Afghanistan – we didn't know what we were doing. What are the demographics of the country? The economic drivers?”[1] If Doug Lute says that we didn’t understand or know what we were doing, then we didn’t understand or know. Such an expression should lead to an underlying logic discussion of what it takes to know what we are doing. In part, it takes an understanding of one’s own and the opponent’s narrative space. To gain that understanding requires study in a variety of topics to include history, philosophy, religion, etc.

Strategy What is strategy? There are multiple expressions of this word. While I may not disagree with many of the points regarding the importance of ends, ways, and means in the calculations of strategy, I disagree with the characterization of the point and purpose of strategy. I am a phenomenologist when it comes to war, as were Carl von Clausewitz and Hans Delbruck and T.E. Lawrence. That means that I try to look at war as a whole – the entire duck as a duck and not the separate elements of a duck – rather than breaking it down to lines of effort and a list of events or actions on each line. I think that T.E. Lawrence gives one of the simplest expressions of strategy in his 1920 article titled “Evolution of a Revolt.” In that article he says, “… strategy, the aim in war, the synoptic regard which sees everything by the standard of the whole.”[2] Lawrence goes on to articulate that in both strategy and tactics he found three elements present: algebraical, biological, and psychological. His expression of his development of strategy in this article is genius and worth your time. The point is that Lawrence identifies strategy as seeing all the actions in the sense of the whole or everything in one as included in the meaning of the word synoptic. The U.S. military regularly confuses doing things with having a strategy. We did a lot of things in Ukraine, Afghanistan, Iraq, Vietnam, etc. but that doesn’t mean that we had a strategy – a singular vision in which all those things worked together to accomplish the overall objective. Strategy is accomplishing and not necessarily doing. It is possible for an actor to accomplish a great deal while doing very little. If one reads and studies Sun Tzu one will see that he regularly advocates for a strategy that allows for just this sort of low ratio between accomplishments and actions. Mentat Training Recommendation If I am right in these three sins, then PME needs to compensate for this failure. In doing so, it is also crucial that PME respond to the ever-decreasing quality of graduate that the secondary and baccalaureate education institutions produce. As the world increases in complexity and academia decreases in effectiveness, there is a widening gap that needs to be closed. Some would have us believe that the way to close such a gap is through AI. I disagree for three primary reasons. One, I agree with Bill Dembski when he posits that there will be no artificial general intelligence (AGI).[3] Two, I think the 2014 movie Ex Machina gives a chilling point that must be considered. The film addresses a sort of Turing Test of whether an AI motivated robot had become sentient. What is learned by the end is that it hadn't really achieved sentience even though by all appearances it seemed to have. In fact, it had simply been executing its programming to deceive someone about being sentient. While I believe that Dembski is correct that AGI is technically impossible, deceptive AGI may be possible. We may be able to deceive others and possibly ourselves about whether a robot, machine, or AGI is sentient and by so doing risk ourselves and humanity. Three, Skynet from the Terminator movies and television series is evil in that humans should never seek nor create a machine mind that does our thinking for us. If you watch Ex Machina, holding to the Skynet is evil paradigm, then it is one of the most significant horror movies ever made as in the film humans plot under computer deception for the death of other humans. That is the worst of all worlds and possibly the world toward which we are heading as militaries develop and test semi-autonomous and moving toward autonomous human killing machines. AI, in general, and AGI, more specifically (though it has general in its name) costs billions of dollars in investment. It is unclear how much money the U.S. Department of Defense is investing in seeking to create something that it may never achieve; however, I believe the DoD may achieve AI in a deceptive and self-destructive way, or it may create forms that only weaken and enfeeble minds and thought processes. It is certain that the money spent on this effort is pointless, at best, and existentially destructive, at worst. The point here is that a portion of this money should be directed toward the development of better thinking humans – the improvement of human intelligence and not artificial intelligence. To what end should that money be directed? What is provided below will be only a brief expression of how the proposed mentat education program might initially be done with the intent to generate conversation and better ideas. I want to begin with the four basic rules that should govern the mentat program:

Next, I offer subject areas that should be addressed. This may not be the comprehensive list, but this is where it should start in the form of foundational understanding of how societies are built, organized, think, process information, make decisions, and go to and fight wars.

Finally, I offer the manner in which these mentats are to be trained. U.S. officers currently enter service to a basic level training that the U.S. Army calls the Basic Officer Leaders Course (BOLC)(almost immediately after commissioning) and they continue to the Captains Career Course (CCC)(about four years after commissioning) and then to the Command and General Staff Officers Course (CGSOC)(about ten years after commissioning). The mentat program would simply piggy-back on the existing PME and be conducted as follows:

I recognize that it will require effort to develop such people. I believe that there are already hundreds of officers who would gladly volunteer to become intellectually elite. For many of them, this is what they hoped for when they took their oath of office. I believe that such a cohort would demonstrate greater value than all the failed investment in AI or AGI and would be more qualified to use whatever technical aids we do develop. Those interested in providing national security in the world as it is and to which it seems to be devolving hopefully will see that the fractional investment in people rather than technology will create the qualitative difference needed for countries to achieve cognitive overmatch of their opponents on the battlefields of the future. [1] Brian L. Steed and Sheri Steed, editors, Voices of the Afghanistan War: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life (Voices of an Era), Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2023, 269. [2] T.E. Lawrence, “The Evolution of a Revolt,” in Evolution of a Revolt: Early Postwar Writings of T.E. Lawrence, University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1968, 105. [3] Bill Dembski, “Artificial General Intelligence as an Idol for Destruction,” billdembski.com [22 January 2024]. https://billdembski.com/artificial-intelligence/artificial-general-intelligence-idol-for-destruction/ [accessed 19 February 2024].

2 Comments

24/2/2024 20:48:21

Great article!

Reply

Brian L. Steed

27/2/2024 18:24:01

Thank you for the thoughtful comments.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorBrian L. Steed is an applied historian, Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed